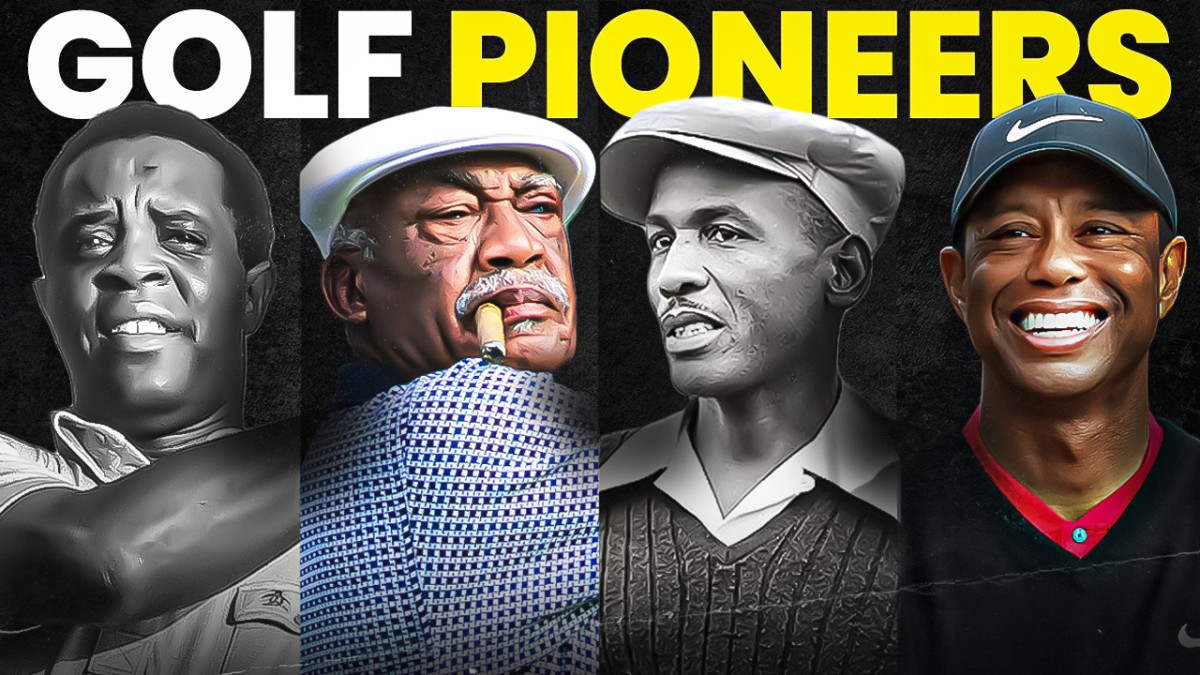

Notable black golfers that were true pioneers on the game include: Dr. George Franklin, George Adams and Robert Hawkins, John M. Shippen Jr, Joe Bartholomew, Charlie Sifford, Lee Elder, Bill Spiller, Renee Powell, Ann Gregory, and Tiger Woods. This is the untold story of black golfers.

Black golfers have had a presence in the game of golf since its early days. The history of black people in golf can be traced back to 1896, when John Shippen became the first black man to play in the national championship, in which he tied for fifth.

From Ted Rhodes to Bill Spiller, Charlie Sifford, Lee Elder, Ann Gregory, and George Franklin Grant, who invented the golf tee in 1899, these unsung heroes are men and women who have paved the way for the extermination of racism in the game of golf. Here’s the untold story of black golfers.

Dr. George Franklin

As we bring you the untold history of black golfers, let’s start with someone whose impact on the game is still in use today. That man is Dr. George Franklin.

Dr. George invented the wooden golf tee in 1899. He took out a patent for this remarkable invention and marketed it, but due to a profound love for the game, Dr. George never sought to earn a penny from his invention. Today, Dr. George’s basic model of the golf tee is still being used in the game.

George Adams and Robert Hawkins

Golf is recognized today as everyone’s sport. In the late 1800’s black people also played the game. But they played in different segregated tournaments and did not enjoy the opportunities, competitiveness, and publicity that whites had.

The United Golfers Association UGA was founded in 1925 by George Adams and Robert Hawkins. The UGA was created for African American professionals. The association operated different professional golf tournaments for blacks during the racial segregation in those times. Players like Charlie Sifford, Lee Elder, Teddy Rhodes, and Bill Spiller were all products of this association.

During those shameful dark times, the PGA fought hard to maintain its all-white status, and black golfers had to play in less than comparable settings. But thanks to the UGA creating its own tour, black golfers could still play the game.

John M. Shippen Jr

John M. Shippen Jr. would be the first black man to play in the national championship.

John was an African American laborer who helped build New York’s Shinnecock Hills course. The second US Open Championship was held in 1896 at Shinnecock Hills, and John managed to enter and play. John Shippen would play impressively, finishing with a tie for fifth, seven strokes off the winning pace.

Click Below To Watch The Full Video

Joe Bartholomew

African Americans have always been involved in golf on and off the course. An example is Joe Bartholomew, born in New Orleans in 1885.

As a seven-year-old, Joe caddied at the Audubon Golf Course. Joe taught himself how to play by copying the swing of the golfers he caddied for. Joe became good at the game, once shooting a 62 at the Audubon club. He became so good that he was instructing others on how to play.

Joe would go on to obtain knowledge in golf architecture, and in 1922, he constructed Metairie’s new course. Scared of people stealing his ideas, Joe would often work through the night under cover of darkness, and everyone was astonished at the course when Joe was finally done with it. However, despite all the hard work and late nights, Joe Bartholomew never got to hit one golf ball on that course.

Joe went on to design and build several golf courses in New Orleans, but he could not play on them. He barely received a salary for his work, and his biggest payoff was from a seven-hole course he built in a property he owned in New Orleans for his friends.

Men like Joe Bartholomew did not get the chance to pave the way for the inclusion of African Americans in golf, despite being influential, but his work in golf course design remains untold.

Charlie Sifford

The name Charlie Sifford is probably a name you’ve heard from the lips of the legendary Tiger Woods and other players.

The answer was a blatant NO when Charlie tried to play with white players. When he politely asked that African Americans be allowed to participate in recognized events solely for black people, he was ridiculed and even received death threats. But Sifford did not give up.

With the support of California attorney General Stanley Mosk, Charlie Sifford became the first black golfer to play on the PGA Tour in 1959.

Charlie Sifford was instrumental in breaking the whites-only clause that the PGA Tour had. He opened the doors of the golfing world to black players, and it is because of him black players like Tiger Woods and Harold Varner the third can play the game today.

Tiger Woods acknowledged in 2015 after Sifford’s death that he might have been unable to play as a professional golfer if Charlie Sifford had given up on his dream to one day play on the PGA Tour. Tiger said his father wouldn’t have been interested in the game of golf if it weren’t for Charlie Sifford breaking the color clause, which may still exist today. Consequently, he wouldn’t be here.

In 2004, Charlie Sifford was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame and was granted the Presidential Medal of Freedom by former president Barack Obama in 2014.

The Masters’ Tournament is Golf’s holy grail. Without playing or winning at the famous Augusta National, a golfer can as well regard his professional golfing career as incomplete.

Click Below To Watch The Full Video

Lee Elder

While Charlie Sifford was the first black golfer to play on the PGA Tour, Lee Elder was the first black golfer to play at the Masters.

In the 1975 edition of the Masters’ Tournament, Lee broke through the race barrier at Augusta National. Lee spoke about his experience playing for the first time at Augusta.

He said as he gripped his golf club in a trembling hand, unsure if he could even perform the task of teeing up the ball, the only thing sustaining him was his faith in God. Miraculously, such trust manifested itself and allowed him to manage the feat.

For the first time in the history of Augusta, a black man walked up to the first tee, not as a caddie, but as a player. That first shot taken by Lee was one heard by the whole world.

It had taken years for Lee Elder to get that defining moment at Augusta. The 60s and 70s were a notoriously unsure period of race relations in the United States, and Lee’s aspiration to do what had never been done before was deemed impossible.

At some tournaments before Augusta, Lee had been refused entry into the clubhouse. At other tournaments, his ball was picked up and hurled into a hedge by a spectator.

When Lee played at Augusta, things changed. He was applauded up to the first tee. Lee’s first shot, a remarkable one which landed in the middle of the first fairway, was applauded by the crowd. For Lee, that applause was reassurance that he was wanted. A reassurance that black golfers had a place in the game of golf.

Before Lee Elder became the first black man to play at Augusta, he became one of the most popular men in golf, and that came with a lot of intimidation and threats. Most of these threats were directed toward stopping him from traveling to Georgia to play. But for Lee, history was going to be made.

Lee earned his place in the Masters after winning a tournament in Pensacola, Florida. Lee played an opening round of 74 for his first time at Augusta. He missed the cut but played at Augusta five times after that first historic visit.

Lee would go on to become the first black man to represent the United States in the Ryder Cup. When he played against the European team in 1979, the US team won 17-11.

At the 2021 Masters, Lee Elder was honored, joining Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player as honorary starters in the ceremonial first tee shot that kicked off the tournament.

Bill Spiller

Golfers like Charlie Sifford and Lee Elder were lucky enough to make a mark on the golfing world, but there were players who were just as good but weren’t so lucky. One is Bill Spiller, arguably touted as the best black golfer before Tiger Woods.

Spiller was a golf protégé from Tulsa, Oklahoma, who refused the usual go-along-to-get-along. A coping mechanism that black golfers use to deal with segregation in golf. There wasn’t much opportunity for Spiller in Tulsa, especially after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Acts of violence like these drove millions of African Americans away from the south. Moving along with the crowd, Spiller left Tulsa for Los Angeles.

While in Los Angeles, Spiller was encouraged to try golf since he was a decorated athlete in his high school at Tusla. Within a few years, Spiller played well above average and decided to play professionally.

However, in the 1940s, golf was still a segregated sport. Spiller played in the UGA and won more than 100 events. But he still wanted to play with the best, and the best players played on the PGA.

Chasing his dream to play with the best, Spiller played in the LA Open and won a spot at the Richmond Open near Oakland, California. This was 1948, and the PGA was still maintaining its Caucasian-only clause.

Spiller arrived at the Richmond Open, ready to play, only to be told he couldn’t play due to the Caucasians-only clause. Alongside the usually non-confrontational Ted Rhodes, who prefers to speak with his club, Spiller decided to legally fight the clause.

Bill Spiller and Ted Rhodes filed a lawsuit against the PGA, citing abuse of power. The PGA countered the lawsuit by promising Spiller that it would end the discriminatory practices if Spiller dropped the lawsuit.

Spiller went on to drop the lawsuit, but the PGA did not uphold its promise. Instead of making their Open tournaments open to everyone, they started using the term Invitationals and ensured black people weren’t invited.

In 1952, Spiller was finally invited to play at the San Diego Open but was turned down by the President of the PGA, Horton Smith. Without mincing words, Smith told the tournament committee that black people would not be allowed to play.

Spiller filed another lawsuit but dropped it again before it got to court. Like before, the PGA agreed to let black golfers compete but did not fulfill its promise.

By 1960, Bill Spiller was way beyond his prime, but he didn’t stop fighting for the rights of Black Golfers. With the help of Stanley Mosk, the California attorney general Spiller caddies for at the Hillcrest country club in Los Angeles, Bill Spiller finally got the PGA to cancel its Caucasian-only clause and help Charlie Sifford make history.

Spiller fought the battles, but Charlie Sifford would take credit for the achievement.

In 2009, Bill Spiller was granted a PGA Tour membership posthumously, and in 2015, he was inducted into the Oklahoma Golf Hall of Fame. Spiller died in 1988, still bitter that he was denied an opportunity to play at Golf’s highest levels just because he wasn’t white.

This story would be incomplete without Renee Powell and Ann Gregory.

Renee Powell

Renee was born to Bill Powell, the black man that built Clearview in 1946. Before seeding that golf course, he had fought in the war in Europe but got no recognition.

Bill Powell loved the game of golf and had played in Scotland when he was stationed there during the Second World War. When he returned home from the war, he couldn’t play, so he decided to make his own course.

Renee Powell was Bill’s youngest child and the second black woman ever to become a full member of the LPGA Tour. Renee was already interested in the sport before she could walk. By the time she was in elementary school, she was hitting at least 500 balls every day.

At 12, Renee competed in the UGA, and at 21, she became the second black woman to play on the LPGA Tour. The first woman was Tennis Star, Althea Gibson. Althea was the first Black woman to compete on the Women’s Professional Golf Tour. In 1966, she ranked 27th in the LPGA.

Renee Powell got her first and only LPG Tour win at 27, at the 1973 Kelly Springfield Open in Brisbane, Australia, but for all of her career, she had to deal with being black.

Ann Gregory

Renee Powell is not the only woman who struggled for the inclusion of black people in golf. Ann Gregory, born in 1912 in Aberdeen, Mississippi, played so well that the newspapers gave her a title, ‘The Queen of Negro Women’s Golf.’

To most people at the time, Ann Gregory was the best African American female golfer of the 20th century. Ann started learning the game when her husband served in the Navy during the Second World War. In 1948, she won a tournament in Kankakee, Illinois. She defeated former UGA Champions Cleo Ball, Lucy Mitchell, and Geneva Wilson in that tournament.

In 1956, Ann competed in the U.S. Women’s Amateur Championship, becoming the first African American woman to play in a national championship conducted by the UGA.

However, after the U.S. Women’s Amateur in 1959, Ann Gregory was refused entry into the player’s banquet at the Congressional Country Club in Bethesda because of her skin color.

While African Americans were banned from playing at the South Gleason Park Golf Course, Ann played that course, saying Tax dollars are taking care of the big course, and there is no way to prevent her from participating. Her actions gave other African Americans the courage to play the course, and that ban was lifted.

In another incident in 1963, Ann was mistaken as a maid by another contestant when she was playing at the Women’s Amateur in Massachusetts. In 1971, she finished runner-up at the USGA Senior Women’s Amateur, becoming the first black woman to do so.

At age 76, Ann Gregory played in a field, competing against 50 women. She managed to win the gold medal in the U.S. National Senior Olympics. She beat her competitor by 44 strokes. In the entirety of her career, Ann Gregory won almost 300 tournaments.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the thought of racism in a gentleman’s sport like golf sounds appalling. However, it wasn’t until 1961 that the PGA of America jettisoned its caucasian-only membership clause.

Tiger Woods

It has been decades since the PGA membership has been made open to everyone regardless of race or origin, yet most golfers on the PGA Tour are white.

Even Tiger Woods still had to deal with racism. In 1997, Fuzzy Zoeller made that nasty comment about Woods, who was 21 then and on a roll to make his monumental win at the Masters.

Tiger Woods has been very cool about these racial slurs and has decided not to make a fuss about the discrimination he has experienced despite his illustrious career.

Instead, Tiger has consistently appreciated the sacrifice that black golfers before him have made just so that the game of golf is open for everyone to play, regardless of their race, color, or origin.

Transcript and video used with full permission from our YouTube channel Golf Plus

Other Related Videos:

- What Tiger Woods Has Been HIDING About His Kids

- Best Celebrity Golfers – Top Ranked

- Tiger Woods RICH Lifestyle Inside Edition

We want to hear from you! Let us know your comments below…

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jim has been an avid golfer and golf fan for over 40 years. He started a YouTube channel called Golf Plus about a year ago and it has been wildly successful. It only made sense to expand and reach more golfers with this site and social media. You can learn more about Jim and Golf Plus Media Group by visiting our About Page.